This post is one in a series on leveraging students’ prior knowledge from experiential learning in your course.

Invite students to co-construct community agreements for classroom conduct

Use students’ previous professional culture experience to develop “community agreements” for classroom behavior, class discussions, or team collaboration. These agreements make explicit the behaviors that students expect of their peers, and agree to engage in themselves, co-constructing a professional environment that will enhance students’ learning experience.

Why co-develop community agreements with students?

Some of the most important work students do in college is that of identity development (Marcia, 1966). In addition to learning new content and skills, they are also learning to understand and redefine themselves in increasingly sophisticated ways, including a view of themselves as members of a profession. Linking this kind of growth to your course by drawing on students’ experiences in professional contexts can help them understand your course as a professional setting, and treat their course learning more like a professional endeavor.

CATLR Tip

Solicit from students some of the ways in which they learned to interact with others professionally and constructively while participating in experiential learning activities. Use the strategies elicited in this way to establish agreed-upon norms of interaction for the classroom. For example, if a student notes that a supervisor intentionally sandwiched negative feedback about job performance between two positive observations, a classroom norm could be that students must say something positive or supportive when disagreeing with another student during classroom discussions.

Learn about your students’ prior experiential learning roles and activities

Even if they are early in the program, your students are likely to have a broad array of work and life experiences, including service learning, dialogue or study abroad, research, and co-op or other work experiences. The roles they’ve played, types of work they’ve performed, cultures and sub-cultures they’ve experienced, and many other aspects of their lives provide many different nodes of connection that you can leverage throughout the semester.

How can prior knowledge assessment enhance teaching and learning in my course?

“Meaningful” learning is learning with many connections to prior knowledge (Ausubel, 1978). These connections help learners organize new information using existing categories and relationships they already understand, giving them a jump-start on the learning process. Learning what prior knowledge and experience students bring to your classroom at the beginning of the semester can help you plan ways to describe and explain your course content in ways that will be most meaningful to the specific students in your room.

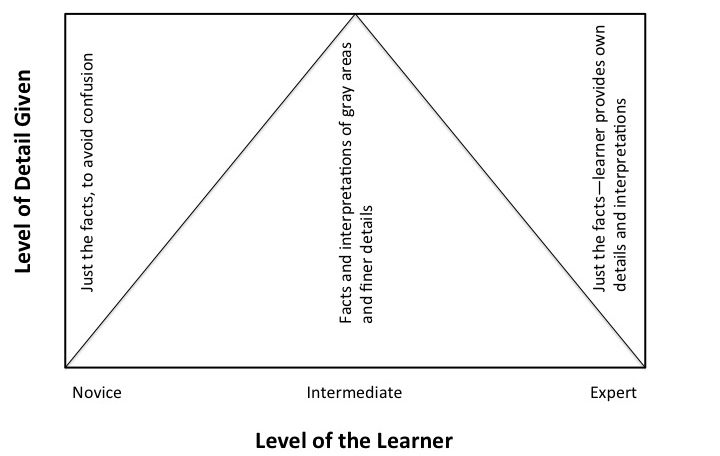

Prior knowledge assessments that are more content-focused can also help you tailor the level of explanation of concepts to be most meaningful to students in the class, which varies according to prior knowledge of that content (Svinicki, 2004). This figure nicely captures a relationship between learner prior knowledge and the level of detail necessary for a given explanation:

CATLR Tip

In the first week of class, give students a brief survey (in class, using Canvas, or as a take-home assignment) asking them about where they’ve done their experiential learning activities and what their role/experience was. You can also ask for specifics about elements that could relate to your course material. For example, in a Sociology class you might ask about the social organization of the offices in which they worked, or in a Calculus class you might ask about any times the organization had to deal with the realities of curves (e.g., arches in buildings, drooping electrical wires, arcs in graphic design, the rise and fall of supply chain efficiencies). Based on the results, spend a few minutes each day planning for how you might use this information in class to connect course material to students’ previous experiences.

References

Ambrose, S.A., Bridges, M.W., DiPietro, M., Lovett, M.C., & Norman, M.K. (2010). How Learning Works: Seven Research-Based Principles for Smart Teaching. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Ausubel, D. (1978). In defense of advance organizers: A reply to the critics. Review of Educational Research, 48, 251-257.

Marcia, J.E. (1966). Development and validation of ego-identity status. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 3(5), 551-558.

Svinicki, M.D. (2004). Learning and motivation in the postsecondary classroom. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.