Developing Teaching & Learning Activities for Grant Proposals, Part 2

The overall goal of a grant proposal is to explain to the grant reviewers and funders how you will use their funding to create an impact on the world. While grants can be focused on creating many types of impact, here we discuss strategies for writing about teaching and learning activities (although many of these ideas will be widely-applicable to a range of grants!)

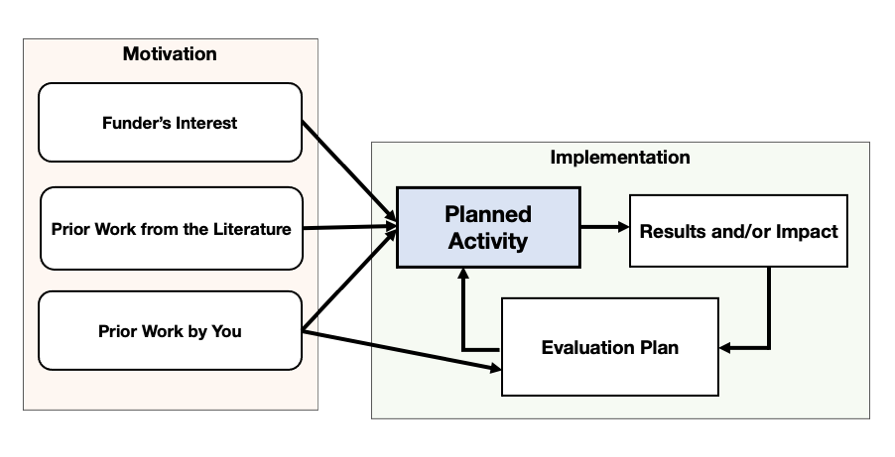

Overall, your grant should address the motivation for why you are proposing a specific activity and your plan for successfully implementing the proposed activity. Throughout your proposal, you should emphasize how your work will help the agency further their mission and achieve their goals.

In sharing the motivations behind your work, your goal is to show reviewers that your idea has a solid foundation in existing work, but also extends existing knowledge in new, innovative ways. To demonstrate that your current ideas are likely to be successful, you should point to things you have already done that have helped you envision and prepare for the proposed activities (even if these are lessons you learned through experiencing or observing failures, it is great to show that you are always innovating!). Additionally, it is important to connect to the literature in a way that demonstrates your familiarity with existing work, your commitment to excellence through scholarship, and your understanding of how to further the field as a whole — by citing current literature, your proposal will demonstrate to the reviewers that you have the key foundational knowledge needed to design and implement your proposed activity.

In addition to carefully laying out the rationale for why you are proposing a specific activity, your implementation plans should include enough detail that the reviewers see you have a solid roadmap forward. You should highlight specific outputs and outcomes that you expect will result from your proposed activity, and which feed into the funders’ goals. By clearly defining the expected impact, you will then be able to include an evaluation plan that outlines how you will know if you’ve achieved your goals. Collecting information about what happened in your proposed activity (e.g., student reflections, a review of student projects) will allow you to share the lessons you’ve learned with others in the field so that they can build on your work. Because things often unfold in unexpected ways, both positive and negative, you may want your assessments to inform changes or improvements to other programs in your context.

While each grant has specific needs, in general these key elements will need to be addressed in most grant proposals related to teaching and learning. Below, we show examples of how others have addressed these topics in successful grant proposals (thank you to those who gave us permission to share their work!), and we offer considerations for you to think about as you develop your grant proposal.

Prior work by you

Sharing about prior work you’ve done and how it relates to the proposed activity is beneficial for many reasons: It shows funding agencies that you are an ideal person to carry out the proposed activities; it highlights your skills and achievements; and it helps show that you are not starting from scratch in this area. Some prompts to consider:

- How does your proposed activity build off of what you’ve done so far and what new things will be created if you receive funding?

- How can you show the grant reviewers that you will be able to achieve the proposed activity?

| Example 1 In this example, the author is showing that his proposed activity builds off of work they have already done at a smaller scale. Describing their prior work in this area gives their project a level of credibility, shows that there’s a foundation for this work, and indicates that they are likely to know what it will take to implement the proposed activity. “The spark for this education program comes from my reactors and kinetics course for juniors and seniors, in which I introduced a series of assignments using the Jupyter notebook, which blends notes and live Python code. Students learned to write scripts, solve coupled ordinary differential equations (ODEs), solve sets of nonlinear equations, and perform nonlinear regression – all while learning chemical reaction engineering. The reception was very positive, but…” |

| Example 2 In this example, the author shows that his proposed activities build off of his ongoing work and he demonstrates (at least anecdotally) that it’s had some impact on his students’ learning and careers. “The PI has been and will continue to remain a strong supporter of publication-level UG research in his group. For example, Mr. [name], working on a project to develop atomically thin sheets of B and N doped graphene, is now a co-author on a currently submitted manuscript at a high-impact journal. Recently, the PI has received an NSF-REU supplement to support Mr. [name] in his research on, “[Title of REU].” |

Connection to existing literature

By showing reviewers how your proposed activity relates to existing literature, you demonstrate that your proposed activities have a theoretical foundation and a potential to expand knowledge in a given topic or discipline. A prompt to consider:

- How does your idea draw from published theories and build off of previously-successful educational activities?

Citing published literature shows reviewers that you are knowledgeable on the subject matter and demonstrates a commitment to making sure your proposed activities have the best chance to succeed. In addition to publications focused on education research, many disciplines have teaching or education-specific journals. Diving into the literature is hard work, but resources from the Northeastern Library can help you get started by finding journals on pedagogy:

| Example 3 In this example, the author describes how their project integrates prior research on instructional strategies into their own teaching practice, and they explain the theoretical reasons why those strategies will support student learning. “During Spring 2013, the PI started implementing a revolutionary method for teaching introductory physics to Engineering Honors students, known as the Peer Instruction method. [citation]… Research has shown that after a few rounds, most students are able to arrive at the correct answers. More importantly, carefully designed tests have shown [citation] that this method can have remarkable effects on the students’ learning abilities, chiefly because students are not afraid to discuss with their peers, and explanations are given by peers who have just recently grasped these concepts.” |

Expected impact and evaluation plan

Be clear about how you expect the proposed activities will benefit learners or other stakeholders, and how you will know if those outcomes were achieved. Additionally, it is helpful to include a plan for how you will identify areas for improvement and how you might modify your activities in the case where you don’t achieve the expected results the first time around. Some prompts to consider as you refine your ideas:

- Have you clearly defined specific, intended outcomes that are observable and measurable?

- What will be different if your funded activity is successful and who will benefit?

- What benefits would you expect in the short-term? Or in the longer-term?

- How will you be able to demonstrate that those benefits occurred?

- Will you measure your outcomes in a customized way, or using existing assessment tools? What modifications might be needed to adapt existing tools to your specific situation?

| Example 4 This example does several things well. The author discusses the methods/tools to be used; defines the goal of the evaluations (i.e., what is the topic and scope of the survey?); and explains how evaluation results will be used for continuous improvement. “Students returning from co-op will complete surveys and focus groups to assess whether the tools they had learned to use the previous semester(s) helped them in their jobs, and if so, how. This formative assessment will allow the materials to be refined. The natural separation into two cohorts (half our students are on co-op in any given semester) will allow quantitative analysis by comparing those with and without the new course materials.” |

Connecting the key elements

Ideally your grant proposal will make it clear for your reader how your proposed activity connects to each of these key elements. If you are addressing education activities as part of your Broader Impacts, you will also want to connect your proposed educational activities to your proposed research!

How CATLR Can Help

CATLR works with educators who are at any phase of developing new ways of educating, particularly for teaching and learning activities that are focused on higher education. Conversations with a CATLR consultant can help you refine your ideas; articulate your learning objectives; navigate the literature on education, pedagogy, and learning sciences; and construct meaningful assessments. While we encourage you to contact us at CATLR at any stage in the grant writing process, asking for assistance well in advance of your deadline (i.e., weeks or months) can allow for early and continuous feedback on your grant proposal.

Ongoing conversations can help both the grant writer and CATLR identify opportunities for collaborations. These collaborations can take many forms, from providing iterative feedback to establishing more formal partnerships such as letters of support or involvement as co-investigators.