I recognized early in my academic career that—to become a better educator and preceptor to pharmacy students—I needed to know more about how people learn. By involving myself in the teaching and learning centers at my previous institution and at Northeastern through CATLR, I embarked on a journey to learn more about the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning.

I recognized early in my academic career that—to become a better educator and preceptor to pharmacy students—I needed to know more about how people learn. By involving myself in the teaching and learning centers at my previous institution and at Northeastern through CATLR, I embarked on a journey to learn more about the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning.

I began by analyzing my teaching evaluations from my experiential pharmacy rotations. One of the most prominent themes was the desire for more constructive feedback. As part of my participation in CATLR’s Teaching Inquiry Fellows program, I read How Learning Works (Ambrose, Bridges, DiPietro, Lovett, & Norman, 2010). I was drawn to the chapter on metacognition and immediately recognized that I could adapt the “Cycle of Self-Directed Learning” framework to create a tool for guided reflection with my pharmacy students.

“I realized that what was important was evidence of expert thinking, not just the general patterns in thinking.”

My reflection tool guides students through a process of assessing the task they performed, evaluating their use of knowledge and skills (what did or didn’t go well), planning their approach for the next time they do something similar, identifying strategies that will help them enact that plan, and anticipating adjustments that might be needed (having a plan B).

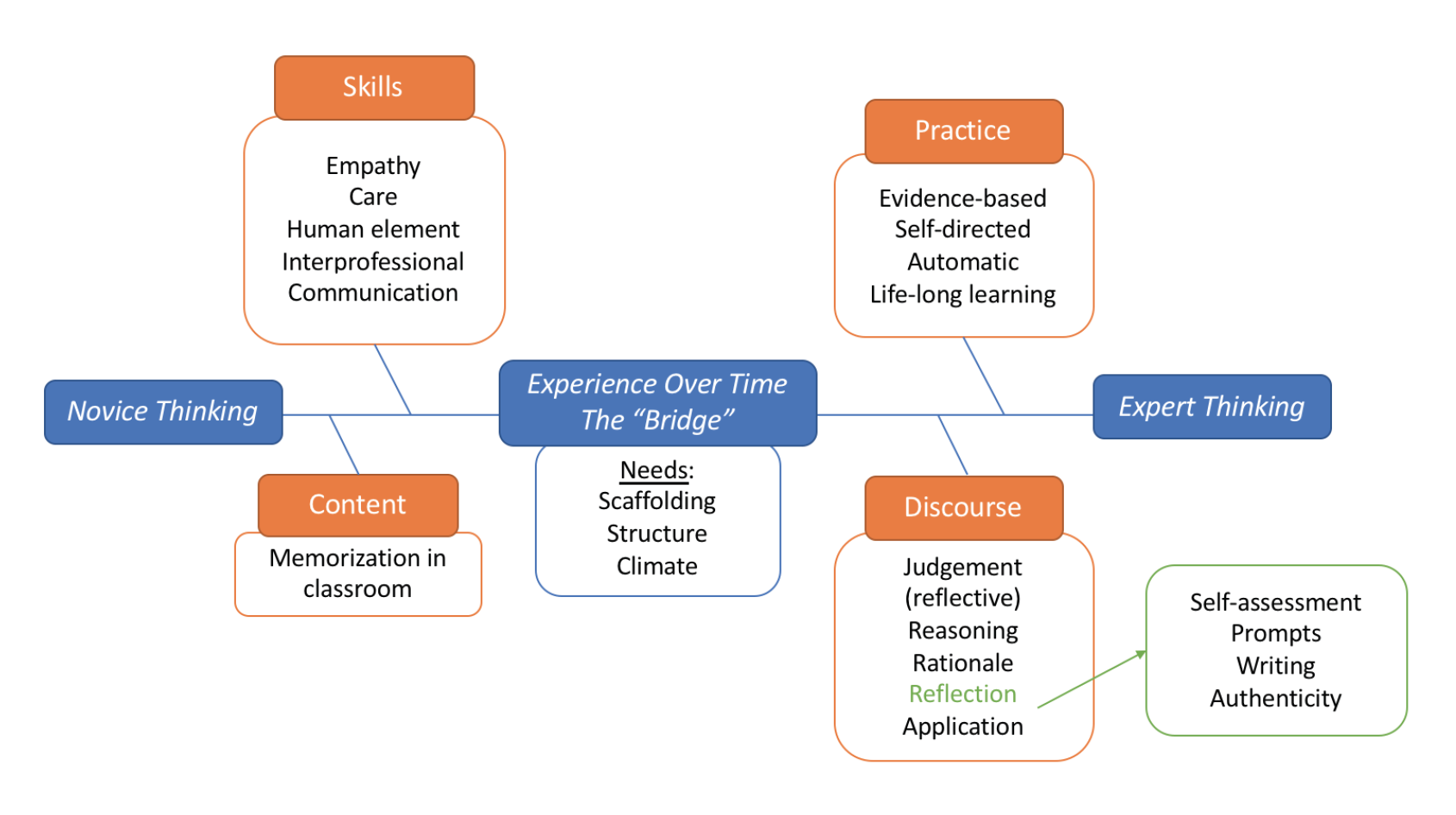

I use the tool to embed student reflection into assignments they complete while on rotation, with the goal of increasing their metacognitive skills and capacity for self-directed learning. This structure also makes it possible for me to provide more meaningful feedback. As a Faculty Scholar, I am looking for evidence that students are crossing the “bridge” from novice to expert thinking. I want to know if they are becoming, in the words of Donald Schön, reflective practitioners (1983).

I have been collecting the reflections for a little over a year. I am now looking at ways to detect if students are thinking “like a pharmacist” by creating a rubric that is grounded in the experts’ perspective. To do this, I met with 16 members of our faculty and posed the question, “What does it mean to think like a pharmacist?” They wrote their answers on sticky notes, with 2-3 comments per person. I am distilling those 40+ comments into a rubric that I will use as a lens for analyzing student reflections. For example, the faculty noted the importance of being detail-oriented, serving as an advocate for patients, and drawing upon research findings to support recommendations for optimizing medication.

I believe that this rubric will not only improve the quality of my reflection analysis, but also be useful to others in my profession.

Across the work I have done as a Scholar, there has been a transformation of my ideas about what I was doing. For example, I didn’t anticipate creating a rubric as a lens for looking at reflections. I thought I would simply look for themes in my qualitative analysis of what students wrote. But I realized that what was important was evidence of expert thinking, not just the general patterns in thinking. The rubric helps me examine student reflections more critically, because it helps me determine if they are reflecting in the ways that are most important to the profession of pharmacy.

Some of the greatest benefits I have derived from the Scholars experience are the opportunity to focus my attention on something I care about, receive feedback from people at CATLR who specialize in SoTL, and also get input from my colleagues in the Scholars program. The connections we formed as a group, across disciplines, helped me bounce ideas off of people with a range of perspectives. I don’t think I’ve ever thought so hard, and I left every meeting feeling incredibly energized.

Resources:

Ambrose, S., Bridges, M., DiPietro, M., Lovett, M., & Norman, M. (2010). How learning works: Seven research-based principles for smart teaching. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Schön, D. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. London: Temple Smith.