The First Artifact of Your Teacher-Student Relationship

The syllabus is the first physical manifestation of how you view your students, how you view your course and discipline, and what students can expect from their time with you. For these reasons, it is important to make your syllabus as learner-centered as possible—giving students the specific information they need in the ways that will most help them engage and succeed in your course.

The Learner-Centered Syllabus

The learner-centered syllabus helps students navigate both the content and processes of a course by focusing on experiences the students will have, rather than what the instructor will do. Such a syllabus helps students understand the context and need for the course, how you personally approach it as a teacher, what the major expectations of the course will be, and how the course will unfold.

Adapted from Grunert O’Brien, Millis, & Cohen (2008)

Each syllabus is a unique document, but common elements include:

- Information about the teaching staff (instructors/TAs)

- Message to students about your teaching philosophy

- Purpose/rationale/context for the course

- Course description

- Course outcomes – what specifically students will have opportunities to learn how to do

- Readings and other resources, including where to get them

- Course calendar

- Course requirements/prerequisites

- Policies and expectations – e.g., late work/make-ups, class participation, academic integrity

- Assessments – types, schedule, and grading procedures

- How to succeed in this course – tools for study and learning this content

Useful Visual Elements

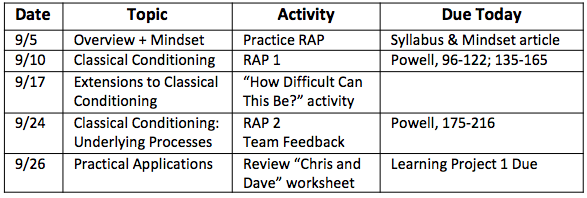

1. Daily Course Schedule

A day-to-day roadmap of what students can expect—and must prepare for—can help them stay calibrated with the pace of the class. It is often the page of the syllabus that students keep visible in notebooks.

A day-to-day roadmap of what students can expect—and must prepare for—can help them stay calibrated with the pace of the class. It is often the page of the syllabus that students keep visible in notebooks.

Putting activities and deliverables on a timeline like this can promote time management, strategic thinking, and self-regulated learning.

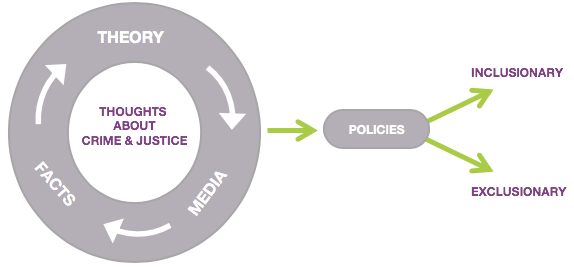

2. Course Knowledge Map

Providing a visualization of “the big picture” of the course—and returning to it regularly—can help students learn important relationships among pieces of content.

This is an important step in the process of growing out of novice thinking and beginning to organize one’s understandings like an expert in the field.

The “Promising Syllabus”

The structure and tone of even well-intentioned syllabi can sometimes make a cold or even punitive first impression of the instructor. Instead, to create a positive course climate, consider crafting a syllabus that makes promises instead of demands. Elements of the “promising syllabus” include:

The Invitation: An invitation to the course and a reason to engage. What kinds of questions does the course explore? For example: “…I invite you to investigate some of these questions. Together we will come to understand…”

The Promise: Promises and opportunities offered by the course, giving students a sense of control over accepting that promise. For example: “My goal for this course is to deepen your understanding of… and you will come to see that…”

Ways to Fulfill the Promise: What you expect of students and how your journey will be organized, avoiding language of requirements. For example: “We all must take responsibility for our own learning. In this class, here’s how we can do that…”

Tracking Our Progress toward Fulfilling the Promise: Specifics on how you will assess student progress and give them feedback.

A “promising syllabus” can include logistical and procedural information that is very similar to traditional syllabi, but always with an effort to describe the experience as something you are embarking upon together. Adapted from Bain (2004)

Syllabus Language Tips

Consider Cool vs. Warm Language Carefully – As an artifact of the teacher-student relationship, your syllabus is often your “voice” to your students. You can include all the information you need while also communicating warmth and respect. Consider the differences between these two statements about make-up exams:

- Cool Tone

No make-up exams will be allowed without documentation of illness, death in the family or other suitably traumatic event.

- Warm Tone

Illnesses, death in the family or other traumatic events unfortunately are part of life. A make-up exam will be given if you contact me within 24 hours and provide documentation.

Want Your Students to Read Your Syllabus? Model that Behavior – Take the time to walk your students through the syllabus on the first day, drawing their attention to important parts and explaining additional context it would be helpful for them to know. This models for them that the syllabus is important enough to spend time on.

On the First Day, Engage Your Syllabus the Way You Teach – For example, if you use small groups, design a group activity in which students discuss your course outcomes. If you use case studies, work a sample case around some central questions of your course. This builds momentum and helps students set realistic expectations (Gaffney & Whitaker, 2015).

References

Bain, K. (2004). What the best college teachers do. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Gaffney, J. D. H., & Whitaker, J. T. (2015). Making the most of your first day of class. The Physics Teacher, 53, 137-139.

Grunert O’Brien, J., Millis, B. J., & Cohen, M. W. (2008). The course syllabus: A learning-centered approach (2nd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.