What is it?

Classroom discussion takes many forms, from whole-class interactive teaching in a large class, to deep dialogue in a seminar, to leaderless conversations in small groups. Regardless of the size or format, certain factors can influence the extent to which a discussion “works” to deepen learning.

What’s the evidence?

Effective discussion demands that we explore our own views in order to articulate them and compare them to others—it forces cognitive elaboration, can reveal the “illusion of understanding,” and has important socio-emotional effects upon learning (Do & Schallert, 2004; Palincsar, 1998; Svinicki, 2004). When discussion is at its best, participants not only exchange information, they also help each other re-interpret their views on the topic at hand. Hibbert, Siedlock and Beech (2016) found that “curiosity-driven dialogue”—as opposed to purely “instrumental information exchange”—has clear benefits upon how learners (a) explore limitations in their knowledge, (b) develop connections with other learners, and (c) develop shared interpretations of the material being discussed. Specifically, they found that while instrumental exchange can lead to an additive process of knowledge sharing where participants emerge individually with larger “toolsets,” curiosity-driven dialogue helped participants re-evaluate what they already knew, open up new horizons of investigation, and engage in more transformative learning.

CATLR Tips

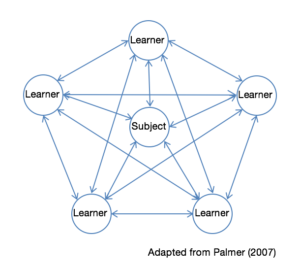

- In a good discussion, everyone is learning—even the facilitator. If interaction becomes a process of students guessing at a right answer, ask them to tell you more about the thinking that is leading them to their answers. Investigating student thinking can bring surprising insights (Palmer, 2007).

- Structure shapes the experience. Good discussions include—but don’t rely on—spontaneous engagement: structure increases the odds of a substantial discussion. Structure can be as simple as a pre-planned list of questions or something more strategic, like decision-making activities where the class must come to consensus on something specific.

- Even brief discussions in pairs or groups can increase engagement. Students can experience class discussion as a kind of public speaking, which commonly causes anxiety. You can help reduce this anxiety by allowing them to talk in smaller groups before speaking to the class as a whole. These activities can be as quick as a 60-second “think-pair-share” or longer, more structured group activities (Ueckert & Gess-Newsome, 2006).

- Waiting has its rewards. When teachers wait at least three to five seconds after a question, they allow time for greater engagement and achievement. Unfortunately, teachers behaving “normally” only tend to wait about one second (Tobin, 1987).

- Accountability for preparation is vital. Good discussion occurs when all participants “bring something to the table.” Accountability activities to ensure student preparation can take place either in or out of class: some teachers require students to bring brief “QQTP” writings that must include a Quotation, a Question, and some Talking Points about the reading (Connor-Greene, 2005). Others use individual-then-team tests, which have been shown to improve individual learning (Vogler & Robinson, 2016).

- Facilitation is a different set of responsibilities and skills than lecture. The facilitator’s role is to create an atmosphere in which students feel it is both expected and comfortable to engage. To achieve this, hold discussions as early as possible in the semester so that this expectation is communicated, and act to prevent students from feeling “shut down” by yourself or their fellow students.

- To generate curiosity-driven dialogue, consider a “barn raising” approach to facilitation. “In frontier America when a family needed a barn but had limited labor and other resources, the entire community gathered to help them build the barn. The host family described the kind of barn it had in mind and picked the site. The community then pitched in and built it. Neighbors would suggest changes and improvements as they built” (McCormick & Kahn, 1982, p. 17). Therefore, in barn raising discussions, ideas are not “owned” but instead launched and improved upon as community property, instead of asserted as “positions” around which individuals assume postures of attack and defense. A ground rule for a barn raising discussion is “[After] you’ve offered the idea, you have no more responsibility for developing it, defending it, or explaining it than anybody else in the group” (pp. 17-18). One way to lead conversation in this direction is to model the de-personalization of ideas using language like: “I’m having a thought that I have some doubts about, but I’m curious what we all think about this: ….” Continually asking what “we” think about various ideas is a way to remind the group of the community enterprise.

Getting started with good questions

| Questions less likely to provoke discussion | Questions more likely to provoke discussion |

|---|---|

|

|

Adapted from Stanford Teaching Commons

Download the Facilitating Discussions brochure.

References

Connor-Greene, P. (2005). Fostering meaningful classroom discussion: Student-generated questions, quotations, and talking points. Teaching of Psychology, 32(3), 173-175.

Do, S. L., & Schallert, D. L. (2004). Emotions and classroom talk: Toward a model of the role of affect in students’ experiences of classroom discussions. Journal of Educational Psychology, 96(4), 619-634.

Hibbert, P., Seidlock, F., Beech, N. (2016). The role of interpretation in learning practices in the context of collaboration. Academy of Management Learning and Education, 15(1), 26-44.

McCormick, D. & Kahn, M. (1982). Barn raising: Collaborative group process in seminars. EXCHANGE: The Organizational Behavior Teaching Journal, 7(4): 16-20.

Palincsar, A. S. (1998). Social constructivist perspectives on teaching and learning. Annual Review of Psychology, 49, 345-375.

Palmer, P. (2007). The courage to teach: Exploring the inner landscape of a teacher’s life. San Francisco, CA: Wiley and Sons.

Svinicki, M. D. (2004). Learning and motivation in postsecondary education. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Tobin, K. G. (1987). The role of wait time in higher cognitive level learning. Review of Educational Research, 57, 69-95.

Ueckert, C., & Gess-Newsome, J. (2006). Active learning in the college science classroom. In J. J. Mintzes & W. H. Leonard (Eds.), Handbook of College Science Teaching. National Science Teachers Association.

Vogler, J., & Robinson, D. H. (2016). Team-based testing improves individual learning. The Journal of Experimental Education. doi:10.1080/00220973.2015.1134420