While classroom norms are baked into the student experience, the online learning environment is unfamiliar for many students and may vary widely across courses. Without the physical setting and the typical face-to-face interactions to guide their learning, students online may have questions such as: What should I be doing right now? Have I completed all of my assignments? How am I doing in this course? How are other students doing in this course?

With intentional design and explicit communication, the educator in the online environment can ensure that students can confidently navigate the course, engage with the content and their peers, and know how to complete their work. Explore the four sections below for ways that you can enhance your students’ online learning:

- Strategies for Organizing and Presenting Content (Video, Audio, or Text)

- Strategies for Helping Students Organize Their Work

- Strategies for Fostering Student Responsibility for Learning

- Strategies for Increasing Student Motivation

Strategies for Organizing and Presenting Content (Video, Audio, or Text)

The most effective online presentations are those that can be easily located, viewed, reviewed, and understood by students. These goals can be achieved by prioritizing the most important concepts (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005), clearly chunking and labeling content segments (Sweller, 1988), prefacing content with an advance organizer (Ausubel, 1960), and using an informal approach. These strategies are described below.

- Prioritize the most important concepts – Apply the Backward Design process to identify the most important concepts for the presentation and tightly align the content to ensure those concepts are clear and not obscured by less important information.

- Chunk and label – Chunking is a strategy for breaking down information into digestible pieces for easier processing by students. Chunk content by organizing it according to meaningful categories, themes, or concepts, and label each segment clearly.

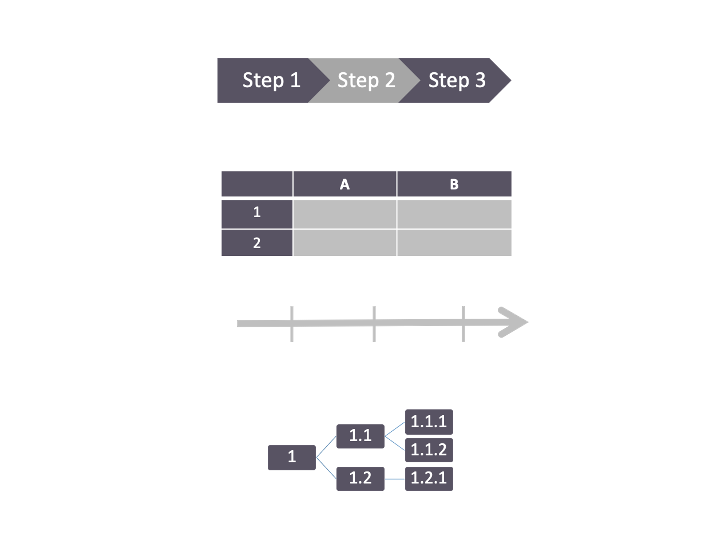

- Use advance organizers – An advance organizer is a visual or text representation of content. Use this tool at transition points in a presentation to help students see connections among segments of related content, such as steps in a process as a sequence, comparison of theories in a table, chronology on a timeline, or components of a system in a diagram (see Figure 1, below).

- Use an informal approach – Students have reported that they prefer informal instructor presentations over those that are more polished. Given this, relax and be yourself when recording yourself speaking (Darby & Lang, 2019).

Strategies for Helping Students Organize Their Work

Course alignment (Biggs, 1996), context for assignments (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005), and consistent week-to-week schedules are features that can help students to not only organize their work, but also better understand the material and have more meaningful and productive learning experiences. Some strategies for achieving these goals include:

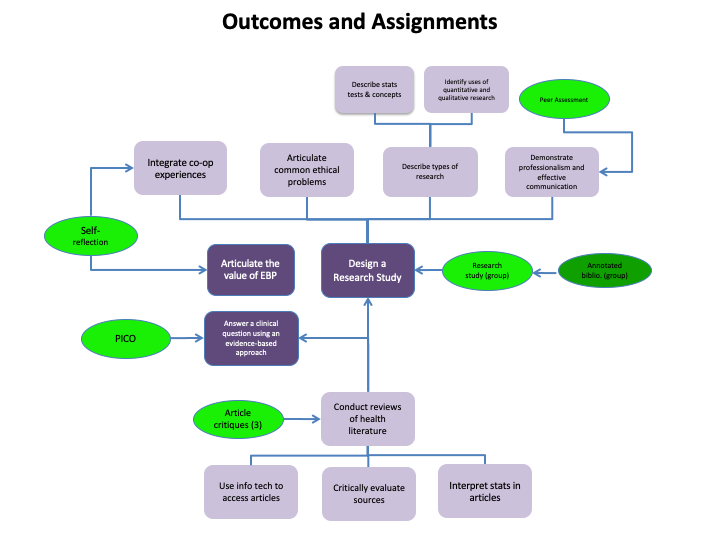

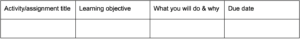

- Create course alignment – When learning objectives, activities, and assessments are in alignment and closely connected, there is course coherence, which can support student learning. Aligning course elements is done through a course mapping process in the planning phase. A simple diagram or table illustrating these connections can help students see the purpose of each assignment (see Figures 2 and 3, below).

- Embed activities and assignments within larger goals or deliverables – Tie assignments together under an “umbrella” goal or project deliverable to provide context and meaning. The smaller assignments then serve as stepping stones (scaffolds) in meeting the larger goal or creating the project deliverable.

- Use a consistent weekly structure and schedule – Create a routine or rhythm by including the same course elements in each module, unit, or lesson, starting and ending modules/units on the same day of the week, and having individual weekly activities (such as reflections or discussion posts) occur on the same day of the week.

Strategies for Fostering Student Responsibility for Learning

Online learning affords students a significant opportunity to develop their learning skills and become responsible for their own learning. Many skills and attributes can play an important role in this process. Examples include comfort with ambiguity, communication, decision-making, help-seeking, independence/autonomy, initiative, inquiry and analysis, mindfulness, problem solving, resourcefulness, and self-directed learning.

To support development of those masteries, educators can employ the strategies below.

- Activate masteries through active learning – Rather than focusing on delivering content, facilitate learning activities that naturally activate the masteries. Example activities include conducting inquiry and analysis, comparing and contrasting, solving problems, drawing conclusions, identifying patterns, and creating products. Focus students’ attention on the masteries by including them in the learning objectives and assessment criteria.

- Explicitly teach specific skills – These skills are important to students’ academic, professional, and personal lives. You can bring students’ attention to them by integrating at least one of them into each assignment or activity, providing examples or modeling of the skills, and prompting students to reflect and record moments on these skills.

- Assign a learning journal – Include a learning journal assignment in which students respond to prompts about their use and development of these masteries, reflections related to successes and challenges encountered, or plans for addressing their challenges.

Strategies for Increasing Student Motivation

Some students may struggle to sustain their motivation to learn in the online environment. Research has shown that student motivation is higher when assignments are relevant and meaningful to students (Wigfield & Eccles, 2000). Further, according to Self-Determination Theory, motivated learners believe that they have the capability to succeed (perceived competence), feel a sense of belonging and connectedness with others in the learning environment (relatedness), and perceive that they have the agency in the learning process (autonomy) (Ryan & Deci, 2000). Below are some strategies you can employ to support each of these motivating conditions.

- Increase perceived competence – Perceived competence can be improved by creating opportunities for practice with feedback, attributing success and failure to effort rather than ability, and focusing on the learning process (within their control) more than the outcomes (not completely within their control).

- Increase relatedness – A sense of relatedness within the online learning environment can be supported by facilitating opportunities for you and the students to get to know each other beyond academic performance, such as sharing hobbies and personal interests. Group projects can also help create connections among students.

- Increase autonomy – A sense of autonomy can be cultivated by giving students choice in learning assignments and activities, giving them voice in course structures and policies, and providing opportunities for them to give feedback about the course.

Related references

Ausubel, D. P. (1960). The use of advance organizers in the learning and retention of meaningful verbal material. Journal of Educational Psychology, 51(5), 267-272.

Biggs, J. B. (1996). Enhancing teaching through constructive alignment. Higher Education, 32, 347-364.

Darby, F., & Lang, J. M. (2019). Small teaching online: Applying learning science in online classes. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Ryan, R., & Deci, E. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68-78.

Sweller, J. (1988). Cognitive load during problem solving: Effects on learning. Cognitive Science, 12, 257-285.

Wigfield, A., & Eccles, J. S. (2000). Expectancy-value theory of achievement motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25, 68–81. http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1999.1015

Wiggins, G. P., & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by design (Expanded 2nd Ed.). Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.