Teaching a Dialogue of Civilizations course is a wonderful opportunity, but can be a daunting prospect for a first-timer.

To support new Dialogue instructors, CATLR and the Global Experience Office partnered to generate this resource, integrating advice from experienced Dialogue instructors and support from learning science literature.

Engaging with a Foreign Culture

A central goal of any Dialogue course is to give students experience engaging with another culture, but some teachers new to the experience wonder how best to plan activities that can best support students across the experience.

Advice from Experienced Dialogue Instructors

Lecture More Early in the Course to give students a familiar, structured experience amidst the otherwise new and unfamiliar environment. (Be sure to take jet lag into account: schedule your lectures for the afternoon for the first few days if necessary.)

Don’t Compete with the Context—As much as possible, tie your course materials and activities to an event or locale related to your Dialogue location. This way, students will see less of a divide between coursework and the cultural experience.

Consider a “buddy system”—If you send students out to interact with locals on their own, consider whether you are comfortable with them going alone or if you want to set up a system in which everyone has at least one partner for these activities.

From the Research Literature

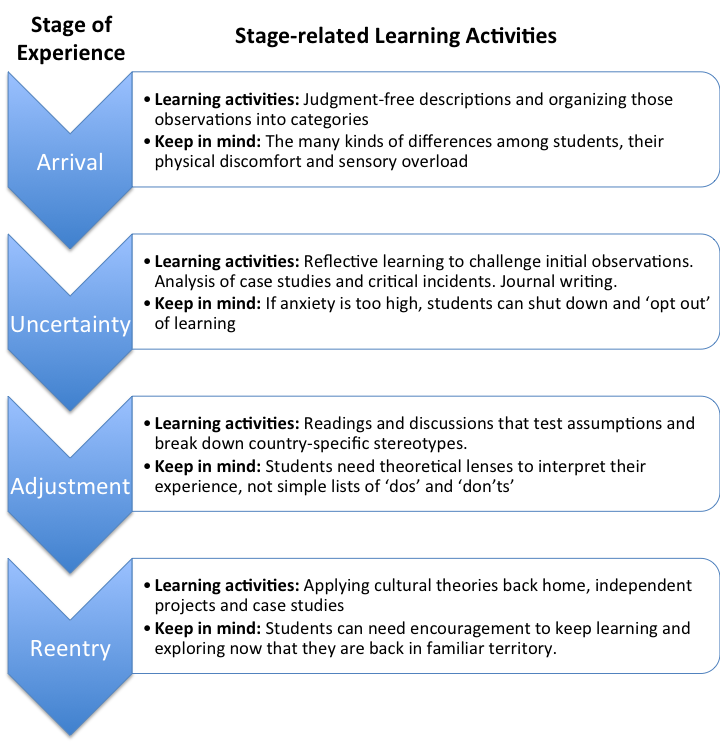

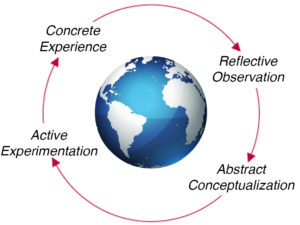

Lucas (2003) developed a framework for cross-cultural instruction across an entire “in country” experience, based upon Kolb’s (1984) experiential learning cycle. This framework describes how the students’ cross-cultural experience can unfold in stages across time, various types of learning you can cultivate at each stage, variables to keep in mind as an instructor, and recommendations for activities along the way.

Adapted from Lucas (2003)

Teaching on a Compressed Schedule

In addition to the very different physical and cultural context, Dialogue courses also teach on a compressed time format which presents its own set of challenges.

Advice from Experienced Dialogue Instructors

“Structure is key for all assignments”—create grading rubrics for everything students turn in, and share those rubrics ahead of time with your students. This not only communicates your expectations efficiently, it also sets you up to grade efficiently while “in country” when time is precious, and communicates that your class is to be taken seriously and is not an easy A just because it’s a Dialogue course.

Assign some readings before departure from the U.S.. Be realistic about this—remember that students are likely still finishing other classes while they prepare for or trip. Assigning no more than 10% of your reading is reasonable, but it can make a big difference on the compressed schedule of the Dialogue experience.

Download what you can before you leave. Internet access can be unpredictable abroad. Save time grappling with these issues by downloading what software and course materials you can to your computer or flash drive before you leave.

From the Research Literature

In addition to reviewing research on compressed format instruction at the college level, Kops (2009) interviewed 27 instructors who had taught at least two semester-long and two compressed courses in the last five years and had excellent teaching reputations. From these sources, he generated these recommendations:

Prioritize what students need to know. Semester long courses invariably need to be reorganized when transitioning to a compressed format. The most complex concepts may need to be front-loaded so that students have the maximum time to engage with the content. The focus should be on “must-know” content, based on the context of the course as an introduction to a field, an advanced major requirement, or as a standard for professional practice.

Rethink coursework. Deconstructing large assignments into smaller, discrete pieces can allow students to receive feedback and respond accordingly at a pace consistent with a condensed course. If longer readings or assignments are expected, scheduling them over weekends or longer breaks between class sessions can give students sufficient time to complete the work without compromising rigor.

Provide additional student support. Despite comparable instruction time, students in condensed courses may need more or different kinds of support to be successful. Increasing your availability outside of class can help provide students the opportunity to get help they need to be successful. Consider providing students lecture notes, presentation slides, or reading guides to keep students on engaged with your instruction instead of focused on note taking during the faster pace of a condensed course.

Teaching an Interdisciplinary Course

Some Dialogue courses are team-taught, with faculty from different disciplines. This can be a challenge for both teachers and students, especially against the backdrop of a foreign culture. This being the case, it’s best to be clear with your teaching partner ahead of time if you want to consider the course multi-disciplinary—viewing similar subjects from different disciplines independently, or inter-disciplinary—using different disciplinary views to synthesize an integrated understanding of the subjects and of the disciplines themselves.

Advice from Experienced Dialogue Instructors

Put “Interdisciplinary” in your course description – Unless it’s made very clear upfront, students can sometimes be surprised by the interdisciplinary demands of a Dialogue course, which can add stress to an already challenging learning experience.

Prepare for widely varying students – In an interdisciplinary class you are of course likely to get students from at least two disciplines. Work with your teaching partner to develop assignments that leverage multiple student backgrounds (e.g., team assignments that make use of both engineering and business expertise, so students come to understand the valuable contributions of their peers in different majors).

From the Research Literature

Get clear on the mission of your course: Mansilla and Duraising (2007) define the “mission” of a truly interdisciplinary course as including (1) the main issue of the course, as well as (2) the reason for an interdisciplinary approach. Golding (2009) provides a brief example: “The mission of this class is to explore the issue of homosexuality. Different perceptions of homosexuality cannot be understood without understanding various disciplinary perspectives on homosexuality. In particular, different disciplines illuminate the reasons behind the perceptions and their history and social consequences.”

Decide ahead of time what “good” interdisciplinary work looks like. Mansilla and Duraising (p.222) offer the following three criteria for considering interdisciplinary student work:

- The degree to which student work is grounded in carefully selected and adequately employed disciplinary insights-that is, disciplinary theories, findings, examples, methods, validation criteria, genres, and forms of communication.

- The degree to which disciplinary insights are clearly integrated so as to advance student understanding-that is, using integrative de-vices such as conceptual frameworks, graphic representations, models, metaphors, complex explanations, or solutions that result in more complex, effective, empirically grounded, or comprehensive accounts or products.

- The degree to which the work exhibits a clear sense of purpose, reflectiveness, and self-critique-that is, framing problems in ways that invite interdisciplinary approaches and exhibiting awareness of distinct disciplinary contributions, how the overall

References

Golding, C. (2009). Integrating the disciplines: Successful interdisciplinary subjects. Melbourne, Australia: Centre for the Study of Higher Education.

Kolb, D.A. (1984). Experiential Learning: Experience as a Source of Learning and Development. Englewood Cliffs, NK: Prentice-Hall.

Kops, B. (2009). Best Practices: Teaching in summer session. Summer Academe: A Journal of Higher Education, 6, 47–58.

Lucas, J.S. (2003). Intercultural communication for international programs: An experientially-based course design. Journal of Research in International Education, 2(3), 301-314.

Mansilla, V.B., & Duraising, E.D. (2007). Targeted Assessment of Students’ Interdisciplinary Work: An Empirically Grounded Framework Proposal. Journal of Higher Education, 78(2), 215-237.