Building a Sense of Belonging and Community into an Online Course

What is it and why is it important to online learning?

Like many aspects of teaching, helping students develop a sense of belonging and community can impact learning in both face-to-face and online courses, but attending to these dimensions in an online course takes intentional planning. When students feel they belong to a class community, they are more likely to be motivated to complete class work, feel safe enough to contribute to discussions, and be open to feedback that can help them improve. Many factors can influence students’ sense of belonging and community, including (but not limited to) student-faculty interactions and student-student interactions, perceptions of stereotyping or tokenism, the tone of how expectations are communicated, and the range of perspectives represented in course materials (Ambrose et al., 2010).

What does the research tell us?

Many strands of research can inform how we think about building community in online courses. We have selected three to describe in this document.

In the early 20th century, Russian psychologist Lev Vygotsky defined the “zone of proximal development” (Flower & Lang, 2019), which he described as the distance between what a student can understand and achieve on their own and what they can achieve with the support of an instructor and peers. For the past century, educators and researchers have been influenced by Vygotsky’s proposition that social interaction is key to effective learning experiences. The implication of the zone of proximal development for online learning is that providing content, assignments, and assessments for students to work through is not enough to deliver a complete learning experience. Rather, faculty must also consider how to integrate peer-to-peer interaction and instructor guidance into learning activities for students to reach their full learning potential.

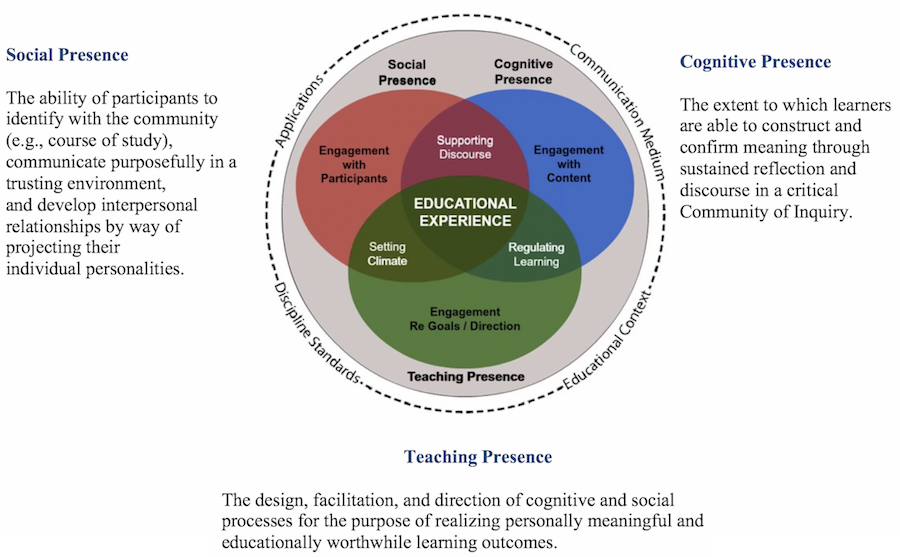

Almost 100 years later, a group of Canadian researchers drew on Vygotsky’s proposition to define a framework for research on and practice of online learning called the Community of Inquiry framework (Garrison, 2011). The Community of Inquiry framework envisions online learning as the intersection of three “presences”:

The COI framework guides online instructors to consider how they are developing a community that supports learning through students’ interactions with content and assignments, their instructor, and each other.

A final framework that is useful in discussing development of community in an online class comes from DeSurra and Church (1994), who defined a 2×2 matrix that categorized learning environments as marginalizing or centralizing and if messages communicating each were explicit or implicit. The original research asked LGBTQ college students to categorize their experiences based on the extent to which students felt their perspectives would be welcomed in a course, but the framework has been extended to a variety of student experiences.

The researchers found that students described the majority of college courses as implicitly marginalizing; in other words, they perceived subtle messages that their perspectives would not be reinforced if shared in class (Ambrose et al., 2010). Most acts of marginalization are unintended, and the following tips can help you consider ways to improve the inclusiveness of your course.

Related strategies for course design

- Design opportunities for peer-to-peer interaction into activities and assignments: In an online version of your course, it may take intentional thought and creativity to build in interaction that will heighten students’ sense of social presence and enrich cognitive presence. Consider ways students could work together on assignments or provide each other with feedback.

Design content with cultural inclusion in mind: Review the cultural perspective of your content. Is it possible to include examples from multiple countries? Can you identify contributions to your discipline from professionals with a range of identities?

Develop introduction prompts intentionally: The first activity of most online courses is introductions. Make the most of this activity by asking students to both connect to course goals and interests. When students begin a course by considering the values they bring to the learning experience, and their goals, they are more likely to persist and succeed (Stanford News, 2017). Consider using video introductions to enhance social presence and make class participants more “real” to each other.

Use a less formal approach in recorded presentations: Research has shown that students have greater learning gains from presentations in which instructors speak more informally and address them personally, as this increases the perception of instructor approachability.

Related strategies for course facilitation

- Use a warm tone and personal language in communications: When emailing students and creating announcements, write as you might speak to students rather than using a formal or academic tone. Use first-person pronouns like “we” and “our” to emphasize class community.

- Demonstrate empathy and care for students: Communicate to students that you are interested in supporting their success. Provide tips for how to do well in your course and clearly communicate how students can connect with you around questions and concerns.

- Help students see you as a “real” person: Share aspects of your personality and background in ways that are comfortable for you and professionally appropriate. This can range from sharing information about personal interests to sharing your enthusiasm for your discipline or your own experiences as a student.

- Let students know that you “see” them: Acknowledge students by using their names in communications and that you have read (or otherwise reviewed) their work by commenting on specific aspects of work. These actions make your teaching presence visible to students.

References

Ambrose, S. A., Bridges, M. W., DiPietro, M., Lovett, M. C., & Norman, M. K. (2010). How learning works: Seven research-based principles for smart teaching. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Cleveland-Innes, M., Gauvreau, S., Richardson, G., Mishra, S., & Ostashewski, N. (2019). Technology-enabled learning and the benefits and challenges of using the Community of Inquiry theoretical framework. International Journal of E-Learning & Distance Education, 34(1). http://www.ijede.ca/index.php/jde/article/view/1108/1733

Darby, F., & Lang, J. M. (2019). Small teaching online: Applying learning science in online classes. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

DeSurra, C., & Church, K. (1994). Unlocking the classroom closet: Privileging the marginalized voices of gay/lesbian college students. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Speech Communication Association. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED379697.pdf

Garrison, D. R. (2011). E-learning in the 21st century: A framework for research and practice (2nd ed.). London, UK: Routledge.

Rourke, L., Anderson, T., Archer, W., & Garrison, D. R. (1999). Assessing social presence in asynchronous, text-based computer conferences. Journal of Distance Education, 14(3), 51-70.

Stanford News (2017, January 19). Brief interventions help online learners persist with coursework, Stanford research finds. https://news.stanford.edu/2017/01/19/brief-interventions-help-online-learners-persist-coursework-stanford-research-finds/