Programmatic Assessment

The programmatic assessment of a degree program evaluates and seeks to understand the ways in which all degree components–degree programs, Cooperative Education, and any other activities–come together to produce cumulative learning outcomes.

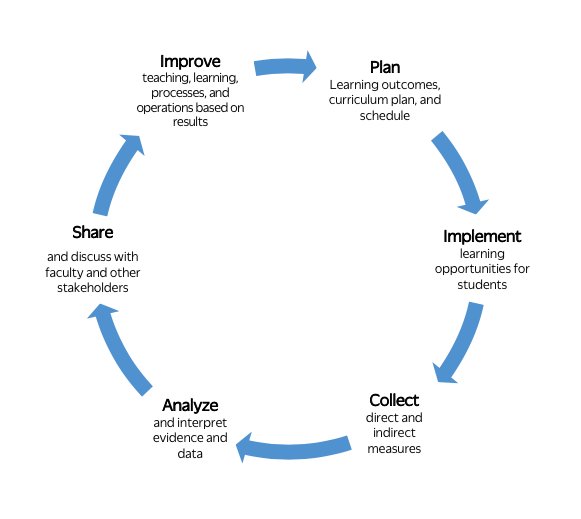

Programmatic assessment is a cycle of inquiry that enables programs to regularly evaluate their goals and the degree to which they are achieving them. During this process, a program uses data to answer questions about how its curriculum supports (and could further support) students’ achievement of identified programmatic student learning outcomes. This process enables the active and strategic iteration of a program’s design to enhance student learning.

“The purpose of assessment is not to gather data and return “results,” but to illuminate ways to strengthen the curriculum, instruction, and student learning” (Pearsons, 2006).

The graphic above illustrates the full assessment cycle, which begins with developing an Assessment Plan at a programmatic level. A complete plan will touch on each element of the full assessment cycle.

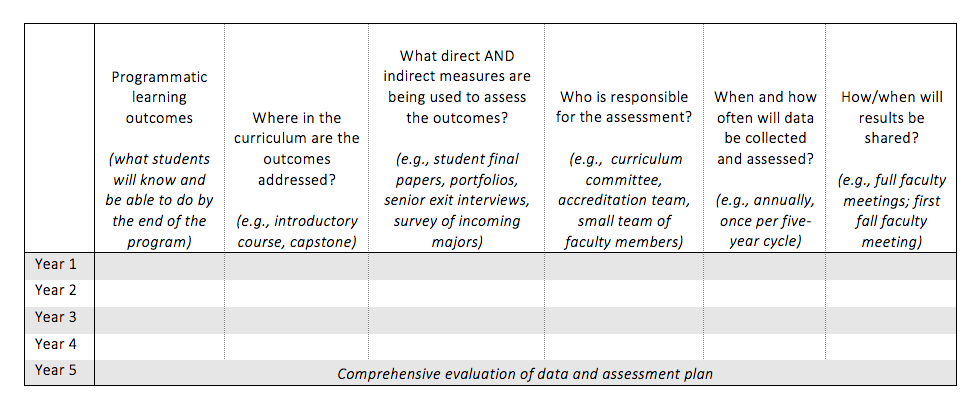

The chart below provides a template for a programmatic Assessment Plan that takes place over a five year period. While this is a common cycle time, your own timeframe may vary. For example, if your program is professionally accredited, the assessment process could be streamlined by following the timing for the accrediting body. Download the Assessment Plan template.

These materials provide definitions and strategies, and address common concerns to help you complete the following steps toward developing a programmatic Assessment Plan:

- Identifying programmatic learning outcomes

- Developing a curriculum map

- Identifying direct and indirect evidence

- Determining who is responsible for programmatic assessment

- Planning when and how to collect and analyze data

- Determining how to share results and make decisions

Programmatic learning outcomes identify the knowledge, skills, and abilities students should possess by the time they complete the program. Specific and unique learning outcomes can help guide programmatic and curricular decisions, such as which courses a student should take and in what order. Given that these outcomes may be used to ground the structure and content of a curriculum, programs benefit when sufficient time and energy are devoted to creating them.

Strategies

Drafting learning outcomes

The process of creating or revising programmatic learning outcomes can take many different forms. Some programs schedule several meetings to brainstorm and then formalize the learning outcomes, while others have a single longer meeting to both refine and finalize. Still others begin by soliciting ideas from faculty (often via a survey) and then use a compiled list of initial ideas to start the in-person conversation. The goal of these steps is to identify the most important knowledge, skills, and abilities the program’s students should be able to achieve by the time of graduation (specific to the program).

Including as many program faculty as possible in the discussion of learning outcomes can increase faculty agreement on the direction and goals of the program, and can provide insights from those directly involved in courses. Broad faculty involvement is particularly important for combined majors, whose programs are striving to weave both disciplines together into a cohesive and integrated program.

Below is a series of prompts that might be used to initiate these conversations.

- Think about the ideal graduate from this program, and the current and anticipated states of the industries where your program graduates most often work.

a. List essential skills for these students to be successful.

b. List necessary discipline-specific knowledge or abilities. - What are the unique disciplinary strengths of the faculty? Which elements are important to what the graduate will be able to do by the time they graduate?

For help facilitating these initial conversations, reach out to CATLR.

Finalizing Learning Outcomes

Initial conversations focus on identifying the most important knowledge, skills, and abilities. After coming to agreement on these, statements should be crafted in a way that expresses the level of mastery that is expected. If you would like, CATLR can help programs determine whether their learning outcomes are measurable and how to describe the level of mastery each requires.

Common Concerns

How many learning outcomes should a program have?

Program directors and faculty can identify as many programmatic learning outcomes as are useful to them. Many programs identify in the range of 5-8 programmatic learning outcomes, which helps to keep the workload of programmatic assessment informative and manageable. Remember that programmatic learning outcomes can and should change over time, so anticipate reconsidering these in the future.

Do we have to assess all programmatic learning outcomes every year?

Many programs opt to identify no more than three learning outcomes to assess per academic year. The order in which outcomes are assessed varies by program. For example, if there are some outcomes that the faculty really need to collect data about to make curricular decisions in the coming year, then programs might prioritize assessing these learning outcomes.

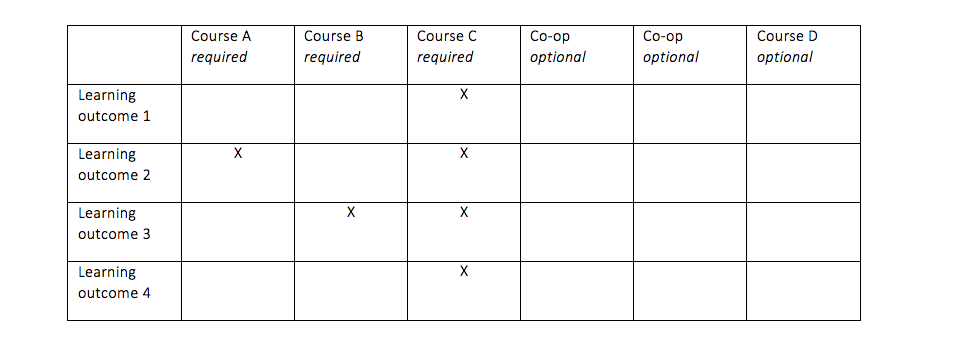

A “Curriculum Map” is a chart or other visual format that shows where in a curriculum each programmatic learning outcome is addressed and evaluated. A simple example is shown below. The left-hand column lists each programmatic learning outcome and each column represents a course or other learning activity. The “X’s” indicate that an outcome is addressed in that experience.

Curriculum map template

Example of a curriculum map that uses degrees of proficiency

Curriculum map for BS/BA Theatre and Game Design

Strategies

When creating a curriculum map, programs should involve as many educators as possible so that instructors, co-op faculty, advisors, etc., can identify how their courses and curriculum activities fit into a sequence and potentially impact student performance in other courses. For example, the educator teaching course C needs to know that their course is expected to guide learners in developing learning outcome 3, and that they can expect students to already have some experience in that outcome from course B.

To create a curriculum map:

- Create a table with a row for each programmatic learning outcome and a column for each course.

- Include all required degree components (courses, dissertation, co-op) to the left and electives to the right. This order will allow you to look at the extent to which all of the learning outcomes are supported for all students regardless of their course selections.

- Columns indicate the programmatic learning outcomes (if any) with which that experience aligns. While some programs choose to mark the learning goals-to-courses correlation using an X (as shown above), your program may move to the next step.

- If your program would like to learn more about the curriculum, mark the level of mastery expected in each course (e.g., introduction, developing, or mastery). This additional level of detail can help represent the cohesiveness of the curricula (e.g., the sequencing of courses, level of mastery taught).

- Finally, identify courses where students produce assignments that may be useful to collect and analyze in the assessment process.

Exploring your curriculum map

The curriculum map can act as a tool to guide important strategic decisions for a program and its curriculum. It can be used to answer a range of questions about the curriculum, such as:

- Are the outcomes addressed evenly throughout the curriculum?

- Are there any courses that are not addressing programmatic outcomes?

- Are there any outcomes that are addressed in few or no courses?

- Are any courses expected to address too many outcomes?

- Is mastery expected without an opportunity for students to develop knowledge, skills or abilities?

- Are knowledge, skills or abilities introduced without opportunity for development or mastery?

- Is there any overlap that is redundant or unnecessary?

Exploring the program’s curriculum map often leads to realigning or modifying the curriculum (e.g., revising course content, adding learning opportunities, reducing redundancy), and sometimes leads to modifying the programmatic learning outcomes. These changes strengthen the program, and are an expected and useful part of the programmatic assessment process.

In programmatic assessment, the unit of analysis is the programmatic learning outcomes, not individual courses or components of the curriculum. There is no one “right way” to measure a learning outcome, and your approach will be informed by your department’s needs, strengths, and overall goals. The strongests assessments will use multiple measures that can be compared or “triangulated.”

In general, there are two types of assessment: direct and indirect – both of which are required by NECHE.

- Direct assessments involve examination of student work to ascertain learning.

- To identify an appropriate assignment or student work product for direct assessment of a learning outcome, you may use the curriculum map to identify the course in which students are expected to achieve and demonstrate their highest level of mastery on that outcome, and select the assignment (project, presentation, etc.) that corresponds to the outcome. Consider selecting something that might represent a similar problem or context that graduates are likely to experience after graduation (Jonson, 2006).

- Indirect assessments involve gathering students’ and sometimes others’ perspectives about student learning through methods such as surveys and interviews (Palomba & Banta, 1999). Although indirect methods are helpful when interpreting the findings of direct assessments, they are not as useful in identifying specific student learning strengths and gaps.

Because each method (direct and indirect) has limitations, each outcome should be assessed using multiple measures (typically a direct and indirect measure), including at least one direct measure. If you can’t identify a relevant direct measure for a particular student learning outcome, determine the reason for this gap (e.g., a relevant artifact is not produced by the curriculum, the outcome is hard to measure), and initiate corresponding changes (revise a course to include a relevant assessment, revise the outcome to be more easily measured).

While departments and programs often collect their own data, the institution (e.g., Office of University Decision Support) also collects evidence related to student learning. Taking advantage of institution-collected data can be an efficient approach to indirect assessment.

Download examples of direct and indirect assessments.

Strategies

Keep in mind that the assessment of student artifacts (work produced by students) is not about evaluating the student, course, or instructor. The focus is trying to provide the program with actionable feedback on the effectiveness of its curriculum.

- In anticipation of using student-produced work products for assessment, think carefully about what and how you collect and store artifacts. For example, are student-produced artifacts enough, or do you also need the assignment description and/or criteria? What additional information do you need to know about the students or the course (e.g., year of study, demographics, sequence of course within the program) to inform the curriculum and its learning outcomes?

- Because programmatic assessment is focused on the program, student work should be de-identified and should only include work products that are pertinent to the outcome of interest.

- Consider utilizing an assessment tool (e.g., rubric) that is shared with all educators and potentially students. While existing rubrics are available from other institutions and research studies, you may choose to develop your own rubric. Visit our course assessment page for more information about how to develop your own rubrics.

- After creating the assessment tool, use the following steps to fine-tune it to your program.

- Seek feedback on assessment tools from colleagues familiar with the learning outcome or discipline.

- Test the tool by having assessors all evaluate the same sample artifacts and then discuss any discrepancies in interpretations of student achievement. This process often leads to adding detail or otherwise clarifying the rubric.

- Establish desired targets, or benchmarks, for each of the measurements. Such targets can be based on things like level of desired expectation; amount of desired improvements from prior years; or national or peer program measures for similar outcomes.

Common Concerns

How many pieces of student work should a program assess for each outcome?

Recommended sample sizes depend on the size of the program and the type of data being evaluated. However, a good measure of whether sufficient data have been included is whether the program would consider making changes to the program based on the identified number of data points. If you choose to assess a sample of artifacts, it is good practice to collect all student work and then select a random sample.

Why aren’t grades considered direct evidence of student learning?

Course grades include many different assignments and activities that may demonstrate student achievement of several different learning outcomes. Furthermore, grades may also include other elements like participation that do not necessarily show students success at learning a particular concept. Finally, standards across courses and faculty are not necessarily consistent. Therefore, grades are not necessarily useful data points for programmatic assessment purposes (Strassen et al., 2001).

Do we need to create new assessment instruments for every outcome?

While a program can create activities, tests, or other add-on assessments for students to complete (e.g., signature assignment, standardized test), programs utilize existing assignments that are already embedded in the program to assess the achievement of learning outcomes.

How do I create a tool that is useful for assessment?

Surveys, exit interviews, and focus groups are often used to collect indirect evidence for assessment. Below are a few types of questions a program might ask different constituents.

Students

- How often did you have the opportunity to achieve the following learning outcomes in your program?

- To what extent to did you achieve the following learning outcomes in your program?

- Describe which experiences you have had this semester that most helped you develop your critical thinking skills.

- What resources did you need to better achieve the programmatic learning outcomes?

Faculty/Staff

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of this specific program as it relates to supporting student learning?

- Please describe the level of preparation (prior knowledge) your students seem to have when beginning this course.

- What are the assignments and/or activities students in this course complete as it relates to the following programmatic learning outcome?

Alumni

- Now that you have been in your nursing position for a year, please rate how prepared you felt on the following topics. (felt very prepared; slightly prepared; underprepared; N/A).

- Compared to your peers, please rate your abilities on the following skills.

- What course or learning opportunity from your Northeastern program has been most useful to you thus far?

- Did this program meet your level of expectation? How so/not so?

While some programs have third parties assess student artifacts (e.g., graduate students, external evaluators), often the program’s curriculum committee or a group of faculty take on this task. Different faculty members may be involved in different steps of the assessment process in order to distribute the workload. Furthermore, different faculty or groups of faculty are often responsible for the assessment process related to different outcomes, with the groups coming together to share findings related to the learning outcome each has assessed.

What types of data should be collected, and when that data should be collected, depends on the assessment cycle that has been planned. Programs often plan to evaluate one or two learning outcomes each year, taking a number of years to complete a full cycle of assessing all outcomes. In the year after an outcome is evaluated, the program may share the data resulting from the assessment and consider changes, if any, that are indicated in response to the findings. This design gives time necessary to collect, assess, and use the data to make informed decisions about the curriculum. Some components of the program may be evaluated once, while others are evaluated every year. The frequency of assessment learning outcomes depends on the needs of the program or could be prescribed by professional accreditation requirements.

When reviewing and analyzing the data, some questions about the curriculum to consider might be:

- What aspects of the program should continue because it is working well?

- What changes need to be made to the program (e.g., format, resources, curriculum, pedagogy)?

Some questions about the learning outcomes and assessment may arise. For example:

- What limitations about the data (e.g., methods, interpretation of data) should we recognize because this may have impacted the interpretation?

- Are the programmatic learning outcomes still worded in the way in which they were intended?

- What changes need to be made to the assessment plan?

- What should be the focus of the next assessment cycle to see if these changes are making a difference?

Programs may also disaggregate data to to identify potential unintended inequities in their curriculum. For example, by examining de-identified student demographics and their relationship to the achievement of learning outcomes, the data could reveal how the curriculum could serve certain student populations better.

Common Concerns

Do I collect data for all of the learning outcomes every year?

There are a number of ways to approach the frequency of collecting data. Some departments have embedded repositories for regularly collecting student work so that when learning outcomes are assessed, there is a body of artifacts that can be randomly sampled from. Data generated from surveys can be collected annually, although some programs do not anticipate changes being observed within one academic year, so they avoid over-surveying students and opt for distributing surveys every other year or with only entering and graduating majors.

How much data do I need to collect?

Programs should collect as much data as they think will be informative about the learning outcome being assessed while being practical and considering resources available to them such as time and number of faculty available. Programs that choose to assess learning outcomes by reviewing student work often collect from all of the courses that map to the learning outcome and then randomly select a manageable, yet representative, number from the population.

Results should be shared with program faculty for interpretation, consideration, and discussion of possible changes to the program. When sharing the results, be sure to share the programmatic learning outcomes, the assessment methods, and the question of interest when examining the data, so that faculty understand any potential limitations to the data. The level of detail included should depend on the audience and their existing familiarity with the assessment cycle.

Using data to inform the program

Based on the results of student learning outcomes assessment, are there things that the program can do to strengthen the program and better support students’ achievement of the programmatic learning outcomes? Realizing that some changes take more time and energy than others, identify next steps in implementing identified changes. This should include any identified changes to be made to the programmatic assessment plan.

Sharing with students and other interested parties

After the faculty and staff have iterated on the program and its outcomes as a result of the assessment process, the results of both the assessment and the resulting faculty conversations and changes might be shared with relevant stakeholders (alumni, students, employers, accreditors). All programs are expected to have their programmatic learning outcomes available on the program website (as part of NECHE requirements). Sharing learning outcomes offers transparency for perspective students, current students, the program, accreditation bodies, and other constituents curious about the program and what it has to offer, and can help programs highlight what makes their program distinctive.

Common concern

Should assessment findings be publicly available (e.g., department website)?

NECHE requires that programmatic learning outcomes, but not assessment plans and findings, are publicly available. However, all assessment processes should be transparent to inform current and future stakeholders about the program.

Beyond learning outcomes: Identifying questions of interest to the program

While assessing the program’s ability to support students’ achievement of the learning outcomes, specific questions of interest to the program can also be explored (Jonson, 2006). Knowing what other questions are important to the program will help determine what data to collect, when to collect it, what criterion or level of mastery is expected, and how the data should be analyzed.

Some example questions are below.

- Since redesigning a fundamental statistics course, are students able to achieve the desired level of quantitative reasoning?

- Do our graduates have the content knowledge similar to those at a peer institution?

- Does the sequencing of courses develop learning outcomes chronologically?

- Is the content that is covered unnecessarily repetitive across multiple courses?

- Has the new service learning requirement improved student learning for this outcome?

- Are employers satisfied with graduates’ the level of clarity in written communication?

- What knowledge and skills do our alumni feel like the program best prepared them for and what are those they wished they knew more?

- How does this combined major compare to other majors as it relates to post graduate job placement; related job placement; and satisfaction with post graduate job placement?

Similar to student learning outcomes, these questions and general outcomes should be articulated on the assessment plan.

Assessment plans are living documents that are modified over time as the program changes (its curriculum, interests, goals, etc.). Also, each cycle through the assessment process reveals new insights into the ways in which assessment can be more efficiently or meaningfully enacted within the context of the program. Consider creating a Canvas site or other archive for notes from faculty members engaged in the assessment process to those who might engage in the assessment process in the future.

- Link to writing learning outcomes

- Template and examples of curriculum map

- Template and examples of assessment plans

- Blooms Taxonomy

- AAC&U rubrics

- Qualtrics to distribute surveys

- Attain program assessment plan (E-series) that was submitted to NECHE by contacting CATLR

References

Eastern Kentucky University Office of Institutional Effectiveness. (n.d.). Retrieved on December 17, 2019 from https://oie.eku.edu/eku-assurance-learning

Jonson, J. (2006). Guidebook for Programmatic Assessment of Student Learning Outcomes. University of Nebraska. Retrieved from https://svcaa.unl.edu/assessment/learningoutcomes_guidebook.pdf

Maki, P. L. (2012). Assessing for learning: Building a sustainable commitment across the institution. Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing, LLC.

Moore, A. A. (2014). Programmatic Assessment for an Undergraduate Statistics Major. Retrieved from https://getd.libs.uga.edu/pdfs/moore_allison_a_201405_ms.pdf

Palomba, C. A., & Banta, T. W. (1999). Assessment essentials: Planning, implementing, and improving assessment in higher education (Higher and Adult Education Series). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, Inc.

Piatt, K. A., & Woodruff, T. R. (2016). Developing a comprehensive assessment plan. New Directions for Student Leadership, 151, 18-34. doi: 10.1002/yd.20198

Stassen, M., Doherty, K, & Poe, M. (2001). Program-Based Review and Assessment: Tools and Techniques for Program Improvement. Office of Academic Planning & Assessment, University of Massachusetts Amherst. Retrieved from: http://www.umass.edu/oapa/sites/default/files/pdf/handbooks/program_assessment_handbook.pdf

Suskie, L. (2009). Assessing student learning: A common sense guide (2nd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Van Der Vleuten, C. P., Schuwirth, L. W. T., Driessen, E. W., Govaerts, M. J. B., & Heeneman, S. (2015). Twelve tips for programmatic assessment. Medical Teacher, 37(7), 641-646. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2014.973388